Florham

- Bobby Kelley

- Oct 8

- 3 min read

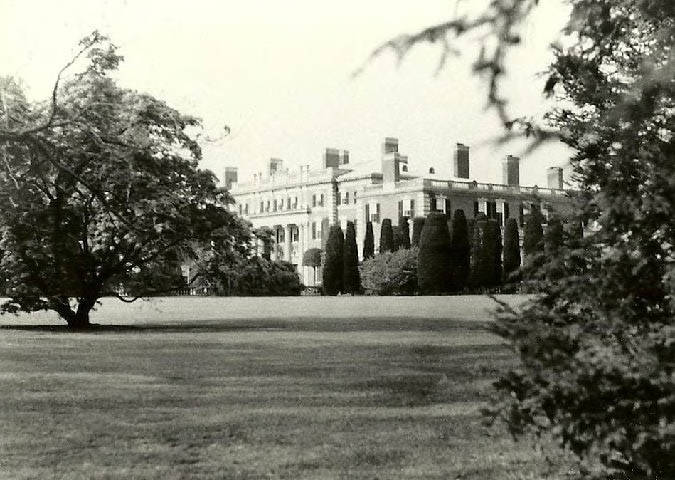

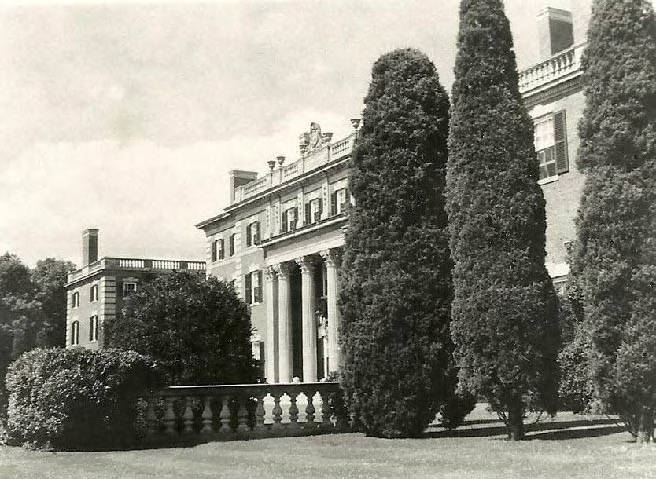

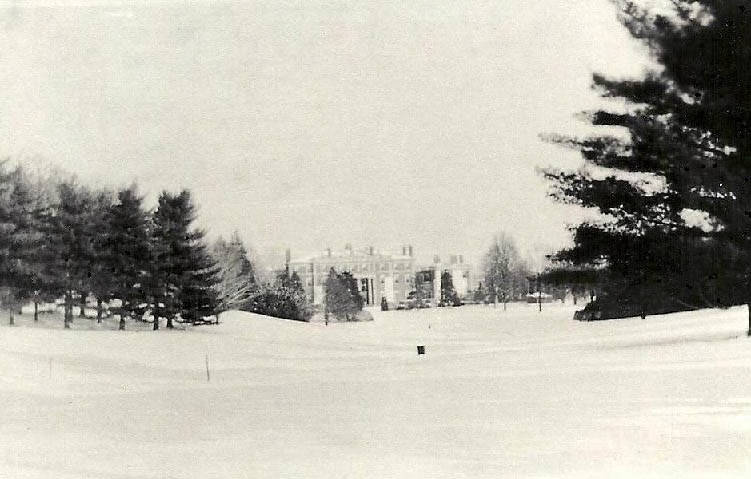

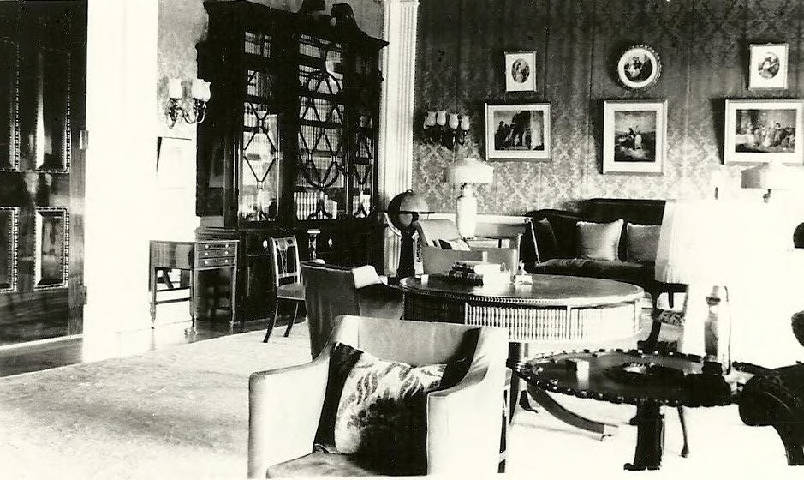

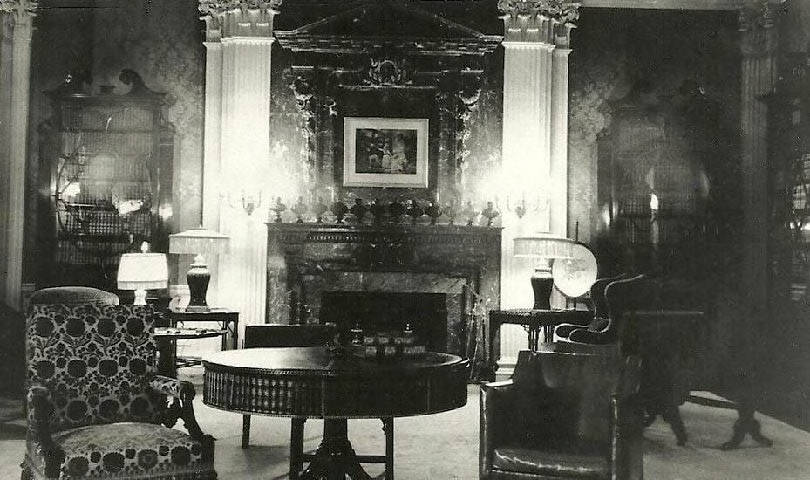

In the early 1890s Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly and her husband Hamilton McKown Twombly assembled farmland straddling Madison and the newly named Florham Park in Morris County, New Jersey, intending to create a country seat to rival the great houses of the Gilded Age. They retained McKim, Mead and White to design the residence and Frederick Law Olmsted to plan the grounds. Work began in the mid 1890s and the family took up residence before the decade closed, giving the estate a portmanteau name that joined their first names as Florham. The main house rose in red brick with limestone trim in a restrained classical idiom, with long symmetrical elevations, high chimneys, and a broad terrace overlooking formal gardens. Inside, suites of reception rooms opened off a grand hall, finishes included marble, carved oak, and decorative plaster, and service areas were organized to support a large household.

Slideshow of exteriors of Florham

By the turn of the twentieth century the estate functioned as a self contained domain. Outbuildings housed stables, carriage and later motor facilities, greenhouses, a powerhouse, and staff quarters. The Olmsted office laid out drives and sightlines that approached the house obliquely, then revealed long axial views across lawns framed by tree belts. The formal garden rooms nearest the terrace used stone balustrades, clipped hedging, and parterres, while the wider parkland transitioned to meadows and woodland. The farm side of the property supported prize livestock and orchards, and the social side supported seasonal entertaining, hunts, and large house parties, all managed by a domestic staff that numbered in the dozens.

Hamilton Twombly died in 1910, and Florence Vanderbilt Twombly kept Florham as her primary country residence for the next four decades. She maintained the house in full order, continued to commission horticultural work on the gardens, and preserved the architectural character of the interiors. During the 1910s and 1920s the house received incremental modernization, with improved heating and lighting and an expanded garage and service court. The landscape matured into the intended composition as Olmsted’s tree plantings reached scale, and the formal gardens were replanted periodically to meet changing taste while retaining their original structure. Through the Depression years the estate remained in operation, albeit with a leaner staff, and during the Second World War some activities were curtailed while the house continued to serve as a family base.

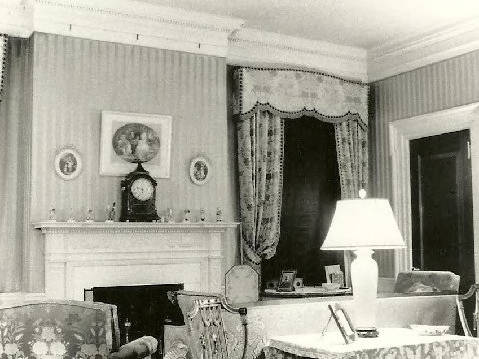

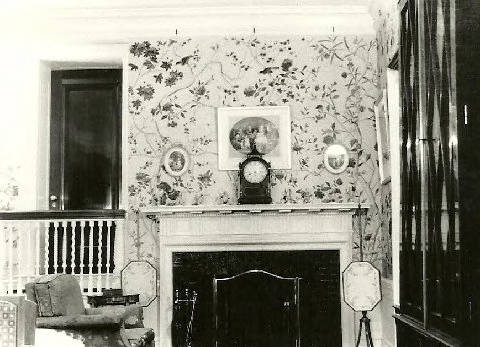

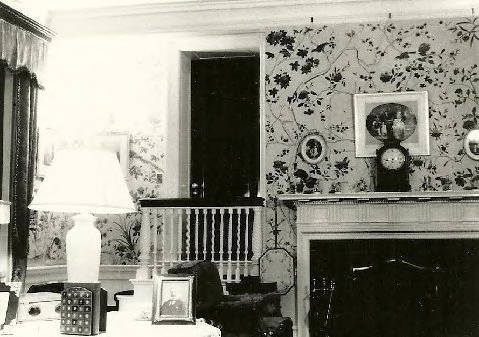

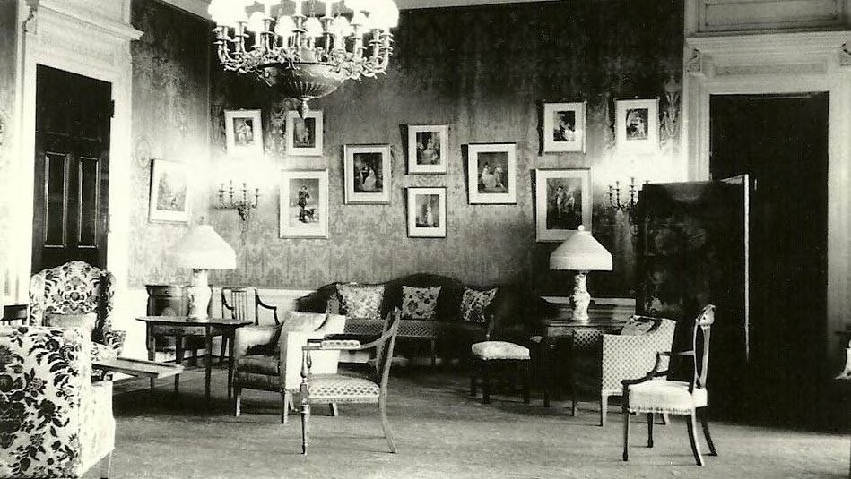

Slideshow of the interiors of Florham

Florence Vanderbilt Twombly died in 1952, and the long process of dispersing the estate began soon after. Furnishings were auctioned, large peripheral tracts were subdivided, and several recreational components evolved into independent facilities. The core house with a substantial acreage survived intact. In 1958 Fairleigh Dickinson University acquired the principal buildings and surrounding grounds to establish its Florham campus. The university adapted the mansion for administrative and academic use, conserving major interiors such as the great hall, the former drawing rooms, and the ballroom, which became settings for campus events and public programs. Carriage houses and service buildings were repurposed for classrooms and support functions, and new academic buildings were placed to respect the historic axes and tree lines.

Slideshow of the playhouse & Grounds of Florham

From the late twentieth century onward preservation and restoration advanced in stages. Friends of Florham, a volunteer organization formed to support stewardship, documented the house and landscape, advocated for sensitive maintenance, and helped guide projects that repaired roofs, restored masonry, conserved ornamental ironwork, and revived garden features. The university reestablished planting schemes in the formal terraces, cleared views that Olmsted intended, and stabilized long runs of historic stonework. Interior work preserved original millwork and mantels while integrating modern building systems. Archival research clarified the sequence of alterations made during the Twombly years and informed choices about materials and finishes during repairs.

A rare look at Florham with Joseph Donon & his wife when it was still the Twombly Mansion

(Joseph Donon was Mrs. Twombly's private chef)

Today the former Twombly mansion stands as the architectural and symbolic heart of Fairleigh Dickinson University’s Florham campus. The building, widely recognized as one of the largest and most complete Gilded Age houses in New Jersey, retains its McKim, Mead and White character in plan and elevation. The grounds still read as an Olmsted landscape, with the approach drives, the framing tree belts, the open lawns, and the terraces that knit house to garden. The estate’s name endures in the campus identity, and the house continues to host academic life, lectures, exhibitions, and community gatherings. Period rooms that once served private entertaining now welcome students and visitors, while the surrounding gardens provide outdoor classrooms and quiet places for study. The continuity of use from private seat to educational institution has underpinned the long survival of both architecture and landscape, and ongoing stewardship keeps the Florham story legible, from its Gilded Age origins through mid century transition and into its present role.

Photos courtesy of Fairleigh Dickinson University Archives

Comments