Knollwood

- Bobby Kelley

- Oct 20

- 3 min read

When Charles I. Hudson began assembling farmland in Muttontown around 1906, he envisioned more than a country retreat. A financier and steel investor who had built his fortune in the industrial boom years, Hudson wanted a home that projected Old World elegance against the rural landscape of Long Island’s North Shore. He called it Knollwood.

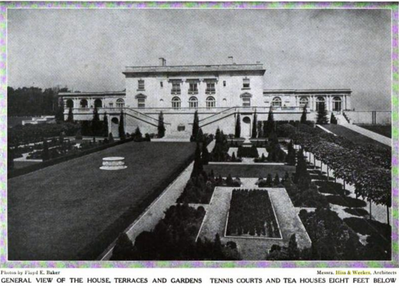

Hudson purchased about 260 acres of former farmland and hired the New York architectural firm of Hiss and Weekes to design a residence worthy of the Gold Coast’s emerging grandeur. The result was a palatial Italian Renaissance–style mansion of about sixty rooms, constructed of stone and set on a rise that overlooked formal gardens and wooded acreage. The architects’ plan balanced classical symmetry with the modern conveniences of the early twentieth century. The north façade was marked by a tall Ionic portico, while the south terrace opened toward the gardens in a sweeping double stairway. The house was surrounded by balustraded walks, pergolas, and terraces that descended to parterres and lawns designed by landscape architect Ferruccio Vitale, whose work at Knollwood ranked among the most refined examples of the American Country Place Era.

Construction began shortly after 1906 and continued through the early 1910s. By 1911, the house and gardens were largely complete and had been photographed for Architecture magazine. The estate included a working farm known as Westbrook, with a Jersey cattle herd, orchards, and a large stable and garage complex that housed horses, automobiles, and staff apartments. Knollwood functioned as both a showcase of wealth and a self-sufficient rural enterprise, a reflection of Hudson’s belief that grandeur and practicality could coexist.

Hudson enjoyed his estate for only a short time. He died in 1921, leaving Knollwood to his heirs, who soon found its upkeep burdensome. The house changed hands in the following years, beginning a new chapter in its history. By the mid-1920s, Knollwood had been purchased by Dr. Nicholas Frederic Brady Webb, a member of the prominent Webb and Vanderbilt families. During the Webbs’ tenure, the estate remained an active social property, appearing in society pages and event listings throughout the 1920s. It was one of the many grand North Shore houses that continued to host formal gatherings even as the age of private servants and vast estates was starting to fade.

By the 1930s, as the Great Depression reduced fortunes and altered lifestyles, Knollwood was again placed on the market. The once-flourishing house entered a quieter phase, passing eventually to new ownership in the 1940s. During this period, the property was acquired by Lansdell K. Christie, a mining executive and real estate investor. Christie held the property largely as an investment and never occupied it as a residence. Without steady care, the buildings began to decline. Vandalism and theft took a growing toll, and the estate’s formal plantings began to revert to woodland.

In 1951, Knollwood briefly reclaimed headlines when it was purchased by King Zog I of Albania, living in exile after his country’s communist takeover. He reportedly paid about one hundred thousand dollars for the property, sparking rumors that the payment was made in jewels and that he planned to establish a royal enclave on Long Island. The reality was less romantic. Zog never lived at Knollwood. Complications with immigration and his failing health kept him abroad, and by 1955 his representatives sold the estate once again.

Years of neglect and vandalism left the mansion in ruin. The empty shell became a magnet for curiosity seekers and treasure hunters chasing legends of hidden royal wealth. In 1959, the once-great house was demolished for safety reasons, erasing its physical presence but not its legend. The surrounding land was later incorporated into the Muttontown Preserve, where traces of Knollwood remain scattered through the woods. The grand double staircase still rises through ivy and leaf litter, the stone kiosks stand roofless among trees, and the gate piers mark the entrance where Hudson’s dream began.

Knollwood’s story mirrors the larger arc of Long Island’s Gold Coast estates—built in a surge of optimism, maintained through extravagance, then undone by changing times and economics. What survives is the sense of scale and imagination that once animated its creation. The terraces still follow Vitale’s geometry, the axial paths remain visible beneath the overgrowth, and the echoes of Hudson’s vision linger in the quiet of the preserve. Once a house of sixty rooms filled with light, Knollwood now lives on in memory and stone, a relic of an era when ambition and artistry met on a hill in Muttontown.

Photos of the ruins are courtesy of Old Long Island

Interesting but sad story. Nice that some things are still there as legacies.