Clarence Mackay and Harbor Hill

- Bobby Kelley

- Nov 4, 2025

- 4 min read

Clarence Hungerford Mackay was born in San Francisco on April 17, 1874. His father, John William Mackay, had begun life in poverty in Dublin and crossed the Atlantic with almost nothing. In Nevada he took part in the discovery of the Comstock Lode, the great silver deposit that changed the economic history of the American West. The mine made him one of the wealthiest men in the country. With that fortune he entered the drawing rooms and salons of New York, London, and Paris. The family lived among aristocrats and industrial figures. Clarence’s childhood unfolded across Europe, surrounded by elegance that had been purchased with hardship now comfortably forgotten.

His early education took place in Paris, under Jesuit instructors who believed that discipline of mind formed character. From there he was sent to Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, England, one of the oldest Jesuit schools in Europe. The school emphasized honor, reserve, and a serious Catholic understanding of duty. These teachings remained with Clarence for the rest of his life. He developed a temperament of quiet formality, measured speech, and an instinct toward loyalty and self-control. He was not raised to create a legacy. He was raised to inherit one and preserve it.

As a young man he returned to America to join the family’s communications enterprises. He became chairman of the Postal Telegraph and Cable Corporation and later guided Mackay Radio and Telegraph. The work was modern and essential at a time when telegraph lines carried the lifeblood of global business. Clarence was not a flamboyant financier. He was steady, deliberate, and respectful of the weight of his father’s achievement.

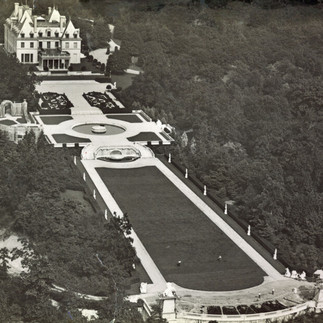

During an ocean crossing in 1897 he met Katherine Alexander Duer, a young woman from a respected New York family. They were married the following year. As a wedding gift, Clarence’s parents gave the couple a high hill on Long Island overlooking Hempstead Harbor. To build their home there, Clarence commissioned architect Stanford White of the firm McKim, Mead and White. White chose to model the central form after the seventeenth century Château de Maisons near Paris. Construction began in 1899. It required years of labor, imported stone, sculpted terraces, and careful placement of gardens and drives so that the house would rise naturally into view.

When it was completed in 1902, Harbor Hill stood among the most impressive private homes in the United States. The estate covered nearly seven hundred acres. The mansion sat at one of the highest elevations of Long Island’s North Shore. From its terraces, one could see the harbor below and the distant line of the Sound. The house was grand, but not heavy. It was balanced and classical, meant to suggest heritage rather than spectacle. Inside, Katherine shaped the interiors, choosing French furnishings, tapestries, and artworks that filled the rooms with cultured presence. Harbor Hill quickly became a setting for concerts, charitable gatherings, and dinners that reflected both refinement and social prominence.

That same year, Clarence’s father died. His passing gave Harbor Hill a deeper meaning. It was no longer merely a wedding gift or social showpiece. It became an inheritance of identity. Clarence now bore the full responsibility of the Mackay name. The house on the hill symbolized not only the family’s rise, but the duty to preserve its standing. Clarence maintained the estate with seriousness and with the belief that stability was itself a contribution to the world around him.

Clarence and Katherine raised three children. Their daughter Ellin would later marry the composer Irving Berlin. Katherine became active in civic and social reform, serving on the Roslyn school board and participating in the suffrage movement. Yet the marriage did not endure. In 1910 she left Clarence, and their divorce was finalized in Paris in 1914. Clarence did not publicly display anger or recrimination. His reaction was private and disciplined. He continued to care for his children and continued to live at Harbor Hill as custodian of the life he had been given.

During these years he formed a lasting companionship with Anna Case, a lyric soprano of the Metropolitan Opera. Their relationship developed gently, with patience, and was marked by mutual respect. Clarence’s Catholic faith prevented him from considering remarriage while Katherine lived. So he and Anna waited. When Katherine died in 1930, Clarence and Anna were married at St. Mary’s in Roslyn in 1931.

To honor the marriage, Clarence presented Anna with a necklace created by Cartier. It held a Colombian emerald of remarkable clarity, surrounded by diamonds. The necklace was not a symbol of grandeur but a personal vow. It represented devotion offered without display. The gift was intimate, the kind that carries feeling rather than pride.

The stability of the Mackay fortune changed after the stock market crash of 1929. Clarence sold much of his art collection to weather the financial strain. Harbor Hill remained, but its upkeep grew increasingly difficult. Clarence’s health began to fail. He withdrew from the large rooms of the mansion and spent time with Anna in the gardener’s cottage on the estate. There, in that small and modest home, he found peace that the great house on the hill had not always provided.

Clarence died in Manhattan on November 12, 1938. His funeral at St. Patrick’s Cathedral included a performance by the New York Philharmonic. He was laid to rest in the Mackay Mausoleum at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn.

After his death, Harbor Hill entered its final chapter. During the Second World War, the United States Army leased a significant portion of the estate. The property that had once welcomed diplomats, musicians, and statesmen was now used for military needs. The mansion stood intact but without the life that had once given it meaning.

By the mid 1940s the estate was no longer sustainable. In April 1947, Clarence’s son ordered the demolition of Harbor Hill. Workers dismantled the stone walls, removed the carvings, and allowed the terraces to collapse back into the hillside. The gardens became open grass. The land was later divided into residential neighborhoods. A few original outbuildings remain, but the house itself is gone.

Photos of Harbor Hill are courtesy of Oldlongisland.com & roslynlandmarks.org

The floorplans and other photos are courtesy of McKim, Mead, & White Archives.

Comments