Myron Charles Taylor: The Quiet Titan

- Bobby Kelley

- Nov 2, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2025

Early Years and Education

Myron Charles Taylor was born on January 18, 1874, in Lyons, New York, into a family of modest means and steady principle. His parents valued education and self-reliance, and these virtues defined him throughout his life. He attended public schools in Lyons before enrolling at Cornell University, where he studied law and earned his LL.B. degree in 1894. Taylor displayed from the beginning a meticulous mind and an unshakable sense of order that would characterize both his professional and personal affairs.

In 1895 he was admitted to the New York Bar and joined the law firm of De Forest and De Forest in Manhattan. His early work centered on corporate and financial law, areas that perfectly suited his analytical temperament. He rose quickly, becoming known for his ability to reorganize and stabilize troubled companies through careful legal and structural reform. His success in practice brought him into close contact with the textile industry at a time when American manufacturing was undergoing rapid transformation.

Marriage, Enterprise, and the Building of Killingworth

On February 21, 1906, Taylor married Anabel Stuart Mack. The couple had no children.

By the early years of the twentieth century, Taylor’s legal acumen had drawn him beyond the practice of law into direct business management. He began acquiring and consolidating textile companies, rescuing several from insolvency and turning them into profitable enterprises. His reputation as a practical reformer grew, and his financial success allowed him to contemplate a life of broader scope.

Around 1922, at the age of forty-eight, Taylor purchased property in Lattingtown near Locust Valley, Long Island, on land long connected with his mother’s family, the Underhills. Rather than demolish the old farmhouse that stood there, he decided to preserve and enlarge it. He commissioned architect Harrie T. Lindeberg to transform the simple structure into a gracious country house of brick and stone.

Photos Courtesy of oldlongisland

The new residence, which Taylor named Killingworth, reflected his taste for refinement without ostentation. Landscape architects Vitale and Geiffert, working with Annette Hoyt Flanders, designed formal gardens, terraces, and a reflective lake that gave the estate its serene character.

Killingworth became the Taylors’ principal retreat from New York. The house contained ten master bedrooms, a long solarium, and rooms arranged for comfort and hospitality rather than display. Here they entertained quietly, hosted family, and welcomed guests from business and diplomatic circles. The estate symbolized continuity between Taylor’s modern success and his ancestral heritage.

In those same years, Taylor’s sense of family responsibility found expression in his establishment of a trust for the maintenance of the Underhill Burying Ground, one of the oldest cemeteries on Long Island and the resting place of his maternal ancestors. The trust ensured that the site would be preserved in perpetuity, reflecting his lifelong respect for history and the enduring obligations of lineage.

Industrial Leadership and Diplomatic Service

By the mid-1920s, Taylor had largely withdrawn from the textile trade and devoted himself to larger corporate and financial endeavors. In 1927 he joined the United States Steel Corporation as chairman of its finance committee. His ability to manage large enterprises soon made him indispensable. When the Great Depression struck, U.S. Steel faced immense challenges, and in 1932 Taylor was appointed chairman of the board and chief executive officer.

He led the company through the darkest years of economic crisis with calm authority and prudence. Avoiding extremes of either reaction or optimism, he restored the confidence of stockholders and workers alike. Under his direction the corporation maintained stability and avoided the turmoil that engulfed much of American industry. Taylor remained at the head of U.S. Steel until 1938, when he retired from active management, having guided the company safely through one of the most turbulent periods in its history.

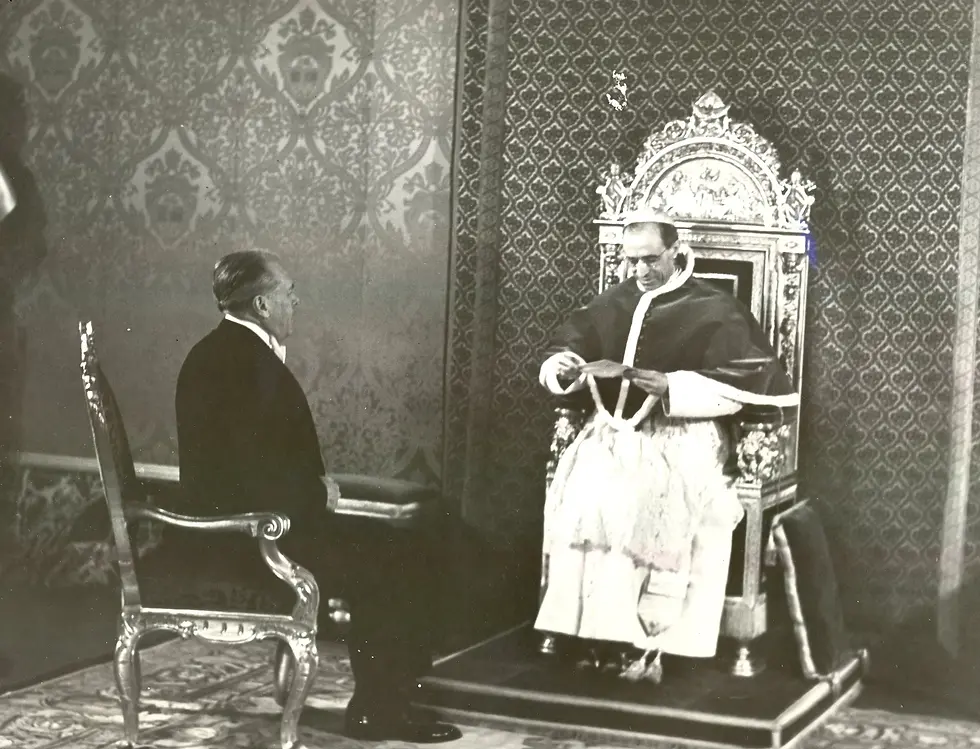

His reputation for balance, judgment, and discretion soon drew him into public service. In 1939 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Taylor as his personal representative to Pope Pius XII at the Vatican. The position carried no official diplomatic title, but it demanded the highest degree of tact and integrity. During the Second World War, Taylor became an essential channel of communication between Washington and the Holy See. He handled humanitarian efforts, aided the coordination of relief work, and served as an intermediary on questions of conscience and diplomacy.

Taylor remained in Rome through 1950, after which President Harry S. Truman called upon him for additional special missions. He served with characteristic humility, completing his assignments quietly and returning to private life when his duties were done. His years in diplomacy deepened his spiritual convictions and confirmed his belief in service as the highest form of responsibility.

Later Life and Death

After his retirement from public life, Taylor divided his time between Killingworth and his residence at 16 East 70th Street in Manhattan, a five-story Spanish-style townhouse facing the Frick Collection. There he maintained his library, art, and correspondence, managing his remaining interests and charitable work with precision.

Anabel Taylor died in December 1958, after more than fifty years of marriage. Myron followed her on May 6, 1959, at the age of eighty-five. His funeral was private, and he was buried beside his wife in Locust Valley Cemetery, not far from the grounds of Killingworth and the Underhill Burying Ground he had endowed.

Legacy

Following his death, Taylor’s affairs were administered with the same order that had governed his life. The Myron and Anabel Taylor Foundation was established to complete his philanthropic program, providing gifts to Cornell University, the Episcopal Church, and major cultural institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Opera. The foundation fulfilled its purpose within a few years and was formally dissolved in 1966.

Taylor’s city residence was sold soon after his death. By 1963 the house at 16 East 70th Street had been demolished and replaced by a cooperative apartment building, marking the end of the old era of private townhouses along that part of Manhattan’s East Side.

Killingworth, however, survived. After Taylor’s death, the estate passed to the Episcopal Diocese of Long Island, which used it for a time as a retreat and meeting center. Maintenance proved difficult, and over the years the property was gradually divided. Portions of the land were sold, but the house itself still stands. Its brick walls remain upright, its chimneys and terraces still discernible, though time has not been kind. The structure endures in a state of severe disrepair, the gardens overtaken by growth, the interiors long unoccupied. Yet the house’s essential form survives, a physical reminder of an earlier age and of the man who built it.

Killingworth Today

The Underhill Burying Ground Trust continues to maintain the ancestral cemetery that Taylor endowed, and Cornell University still bears his name in the law school building he gave it in 1932. Through these institutions, as well as through his quiet example of integrity, Myron Charles Taylor’s influence endures.

He lived without extravagance and led without noise, preferring usefulness to notoriety. His career spanned law, industry, and diplomacy, yet the values that governed each were the same: duty, order, and faith. Killingworth, standing still against the passage of time, remains a fitting symbol of its builder — enduring, dignified, and steadfast.

Comments